Cosmology, consciousness, and the Ātma Paradigm

Modern science is one of humanity’s most extraordinary achievements. In just a few centuries, it has transformed our understanding of the universe—from the motions of planets to the large-scale structure of the cosmos, from the behavior of subatomic particles to the evolution of galaxies across billions of years. And yet, the deeper science progresses, the more evident its conceptual boundaries become.

This is not a failure of science. It is a sign of its maturity.

Science excels at describing how phenomena behave. It models regularities, extracts patterns, and formulates predictive laws. But when we ask what reality ultimately is, or why anything exists at all, science reaches a horizon it cannot cross on its own. The Ātma Paradigm begins precisely at that boundary—not to oppose science, but to complete its explanatory scope.

Gravity: a perfect description without an explanation

Consider gravity, one of the most fundamental phenomena in cosmology. For over two centuries after Isaac Newton, gravity was understood as a force acting instantaneously across space. Newton’s equations worked astonishingly well, allowing precise predictions of planetary motion and celestial mechanics. Yet Newton himself was deeply uncomfortable with the idea of “action at a distance”. His theory described gravity’s effects, but not its essence.

This conceptual gap became even clearer with Albert Einstein. In general relativity, gravity is no longer a force at all. It emerges from the curvature of space-time caused by mass and energy. Planets orbit stars not because they are pulled by an invisible force, but because they follow geodesics in a curved geometry.

General relativity has passed every experimental test to date, from the precession of Mercury’s orbit to gravitational lensing and the dynamics of stars near the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. And yet, even now, physicists openly acknowledge a striking fact: we still do not know what gravity is.

We can model its behavior with extraordinary precision. We can simulate entire universes governed by Einstein’s equations. But the ontological nature of gravity—what it is at its core—remains unknown. This distinction between description and explanation is not incidental. It runs through the very foundations of modern cosmology.

Cosmology and the question of “why”

Cosmology offers another powerful illustration. The standard cosmological model successfully describes the expansion of the universe, the cosmic microwave background, the formation of galaxies, and the large-scale structure of matter. Yet when cosmologists trace these equations backward in time, they encounter singularities, horizons, and limits beyond which the theory no longer applies.

What caused the Big Bang? Why do the laws of physics have the form they do? Why do fundamental constants appear finely tuned for complexity and life? These are not marginal questions. They are central to our understanding of reality, and yet they fall outside the explanatory reach of physics as currently practiced.

As explored in Metaphysics in the Age of Physics modern cosmology frequently crosses into metaphysical territory—often without acknowledging that it has done so. Multiverse scenarios, brute facts, and accidental universes are not empirical results; they are philosophical interpretations layered onto scientific models.

The Ātma Paradigm invites us to make these underlying assumptions explicit and to examine them with care. It does not question the value of empirical data or the power of mathematical models, but it does call for greater clarity when those models are interpreted in ways that quietly drift into philosophical territory, often without being recognized as such.

Quantum theory and the problem of observation

Nowhere is this need clearer than in quantum mechanics. In experiments such as the double-slit experiment, particles behave like waves until measured, at which point they appear as localized particles. The outcome depends not only on the system, but on the act of observation itself.

As Werner Heisenberg famously noted, what we observe is not nature “in itself”, but nature as revealed through our method of questioning. The observer is no longer a passive spectator, but an integral part of the phenomenon.

This presents a profound challenge to classical materialism. If physical reality behaves differently depending on observation, what does “physical” even mean? Is matter truly fundamental, or is it relational—defined in part by interaction, context, and awareness?

Quantum theory does not answer these questions conclusively, but it makes one thing unavoidable: the observer cannot be ignored.

At this point, a crucial distinction becomes unavoidable: the difference between meaning and the symbols through which meaning is expressed (see also Does the Universe Need an Observer?). As conscious beings, we do not share meaning directly. Meaning arises within awareness, but in order to communicate it, we must translate it into symbols—sounds, words, mathematical equations, diagrams, or images.

These symbols are not the meaning itself; they are representations, approximations that point toward it. Confusing the two leads to serious misunderstandings, both in everyday communication and in science. In physics, mathematical formalisms are extraordinarily powerful symbolic languages, but they remain descriptions, not reality itself.

Quantum mechanics makes this limitation explicit: the act of observation mediates what can be known, and measurement does not reveal nature “as it is”, but nature as it appears through a specific experimental and conceptual framework. In the same way, symbols mediate meaning without ever exhausting it. Recognizing this distinction is essential, because it mirrors the deeper epistemological divide between nature and the observer of nature. Consciousness is not one symbol among others, nor a byproduct of them; it is the very ground in which symbols acquire meaning and through which reality becomes intelligible.

The Ātma Paradigm: consciousness as foundational

The Bhāgavata tradition offers a radically different starting point. Instead of treating consciousness as a late-stage byproduct of matter, it treats consciousness as ontologically primary. Matter, energy, space, and time are real—but they are not self-sufficient. They operate within a deeper framework grounded in awareness.

The Ātma Paradigm articulates this through a clear ontological distinction:

- The physical body, governed by material laws

- The subtle mind and intellect, mediating perception and cognition

- The ātmā, the irreducible conscious self

This model does not deny physical causality. It situates it. Chemistry can explain molecular interactions; neuroscience can map neural correlates; but neither can explain why subjective experience exists at all. Consciousness is not something matter accidentally produces but the very condition that makes experience, meaning, and knowledge possible in the first place (for more on this topic see The Hard Problem of Consciousness and the Primacy of the Ātma).

From this perspective, the unresolved questions of cosmology are signposts pointing beyond reductionism.

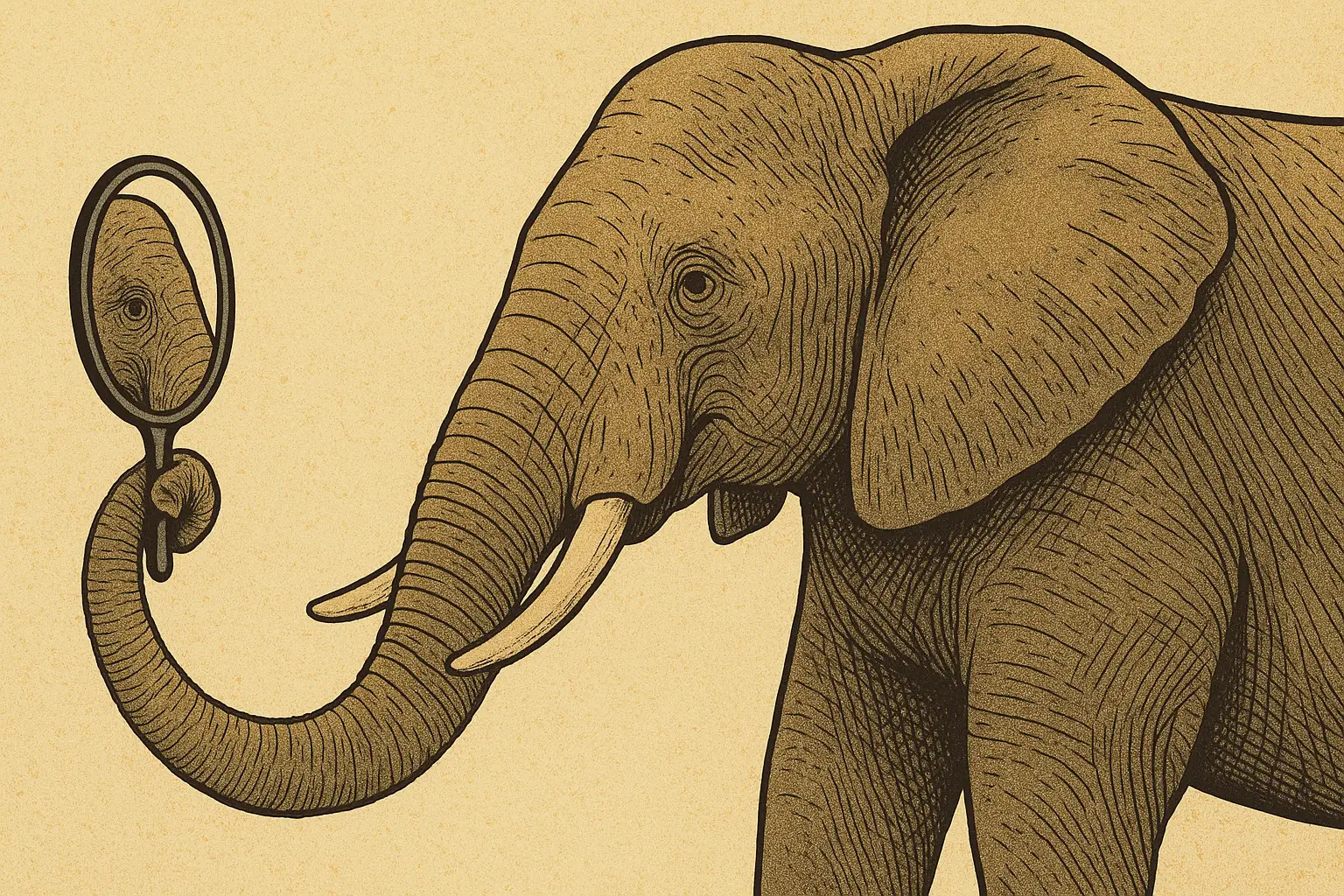

Knowledge as a participatory process

One of the most distinctive features of the Bhāgavata epistemology is its recognition of the knower as part of the knowing process. Knowledge is not merely extracted from an external world; it is shaped by the state, clarity, and orientation of consciousness itself.

This insight resonates strongly with contemporary physics. In quantum theory, measurement affects outcomes. In cosmology, the observable universe is limited by the observer’s horizon. Even the concept of time becomes relational and emergent rather than absolute.

The Bhāgavata tradition anticipated this relational structure long ago with the epistemology of the three pramanas. It does not separate inner and outer knowledge, science and self-inquiry. Instead, it integrates them into a coherent framework in which understanding the cosmos and understanding oneself are inseparable processes.

Toward a new synthesis

What is needed today is not less science, but deeper literacy—both scientific and philosophical. Science must remain rigorous, empirical, and self-critical. Philosophy must remain precise, disciplined, and informed by scientific discoveries. And metaphysics and subjective knowledge must no longer be treated as a speculative luxury, but as an essential component of a complete worldview.

The Ātma Paradigm proposes such a synthesis. It offers a framework in which cosmology, physics, and consciousness studies can coexist without reduction or conflict. It allows us to appreciate the extraordinary power of scientific models while acknowledging their limits. And it restores purpose, meaning, and subjectivity to a universe that has too often been described as indifferent and accidental.

Science tells us how the universe behaves. The Bhāgavata wisdom asks a deeper question: who is the universe for, and who is asking the question in the first place?

Only by holding both inquiries together can we begin to approach a truly complete understanding of reality.