The triumphs and limits of science

Science is one of humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements. It has carried us to the moon, sequenced the human genome, mapped the cosmic microwave background, and revealed the hidden order of quantum fields. It explains how stars are born, how galaxies form, how atoms combine to create the visible world.

Science excels at answering questions like:

- What is happening?

- How does it work?

- What patterns can we observe?

Take gravity as an example. From Newton’s equations to Einstein’s relativity, we can model its behavior with stunning precision—predicting planetary orbits, designing spacecraft trajectories, even detecting gravitational waves from distant black holes.

And yet, despite centuries of study, we still don’t know what gravity is. We describe how it behaves, but not why it exists in the first place.

The same holds true for many phenomena. Science offers models, not ultimate causes. Its strength lies in description, not in answering the deepest questions of existence.

The limits of description

Philosophers of science describe this limitation as the underdetermination of theory by data: different, even contradictory theories can often explain the same evidence. This means scientific models are always provisional, effective within their scope, but not exhaustive.

Science also brackets out the observer. It assumes that reality can be studied as if independent of the one perceiving it. But quantum physics has forced us to reconsider:

- What we see depends on how we look.

- What we measure depends on what we ask.

- What we conclude depends on what we assume.

This reveals a profound truth: science is not epistemologically self-sufficient. It relies on philosophical assumptions it cannot prove—such as the reliability of logic, the stability of laws, and the very existence of an external world.

When scientists forget this, they risk slipping into amateur philosophy, making metaphysical claims under the guise of empirical authority.

Philosophy: asking the deeper questions

This is where philosophy becomes indispensable. It asks questions science cannot resolve:

- What is existence?

- What is consciousness?

- What makes something meaningful?

- What counts as knowledge?

The problem is that philosophy in the modern age is often fragmented, skeptical, and detached from lived practice. What is needed is a philosophy that integrates knowing with being—that connects truth with transformation.

These are not “secondary” concerns. They are the foundations on which science itself rests. Without them, we cannot define what science is or what it seeks.

Bhāgavata insight: consciousness and purpose

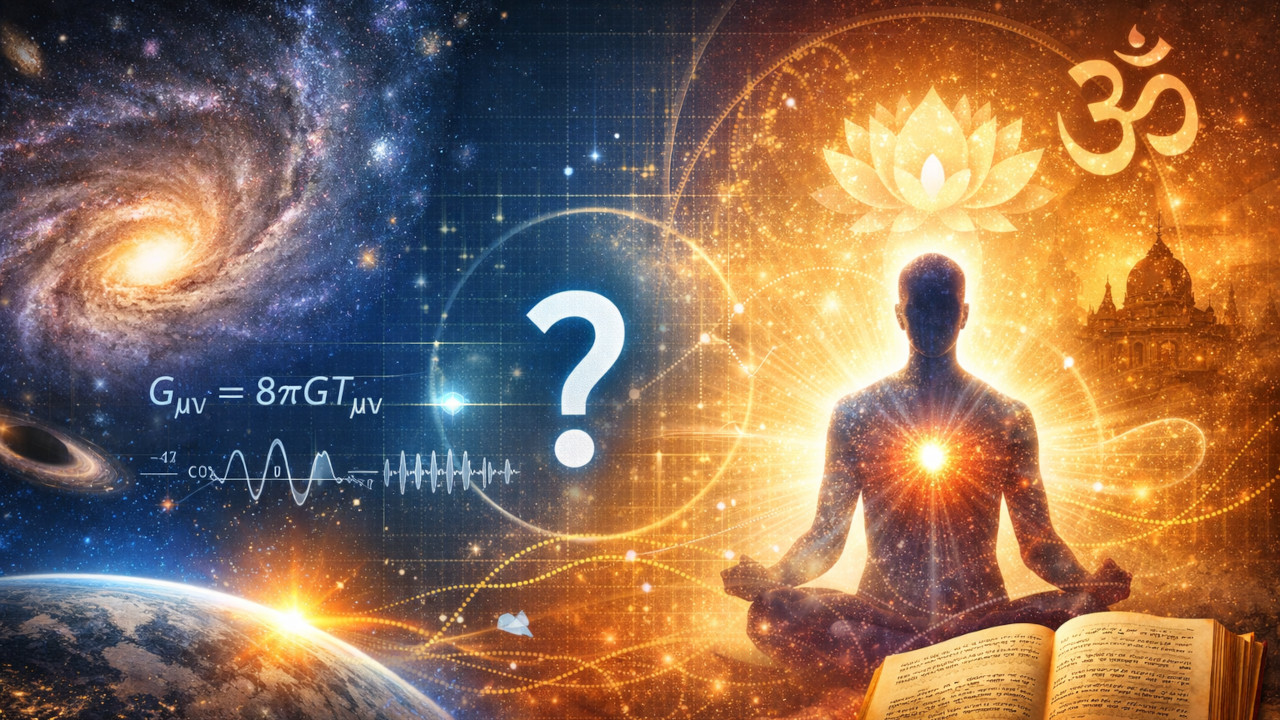

The Bhāgavata tradition offers just such a framework. It accepts the strengths of science but situates them within a broader metaphysical vision. Knowledge arises from three complementary sources (pramāṇas):

- Pratyakṣa (direct perception): empirical observation through the senses.

- Anumāna (logical inference): reasoning based on evidence.

- Śabda (authoritative testimony): revealed wisdom transmitted through realized teachers and scripture.

Together, these provide not only information but orientation.

In the Bhāgavata view, consciousness is not a byproduct of matter but a fundamental principle of reality. The self (ātman) is eternal, irreducible, and self-luminous. Far from being a biochemical accident, human awareness is central to the cosmos.

The Bhagavad-gītā affirms this in striking terms:

“For the soul there is neither birth nor death. He is unborn, eternal, ever-existing, and primeval. He is not slain when the body is slain.” (2.20)

Here, existence is not reduced to matter. Consciousness is not explained away but honored as the foundation of all experience.

This perspective transforms the ultimate “why” questions:

- Why consciousness? Because it is intrinsic to reality.

- Why these laws of nature? Because they serve as the stage for conscious beings to evolve in knowledge and love.

- Why meaning, beauty, and love? Because they are not accidents, but reflections of the soul’s eternal nature.

Toward a spiritual science

If we truly want to know why we exist, we must go beyond description. Science is indispensable, but it is not sufficient. What is needed is a spiritual science—an integrated pursuit where:

- Science provides clarity of observation.

- Philosophy provides depth of interpretation.

- Spirituality provides orientation and purpose.

In the Bhāgavata model, knowledge (jñāna) is not merely descriptive but transformative. A realized knower is called tattva-darśī—one who “sees truth as it is.” This vision is not achieved by instruments alone but through purification of consciousness, humility, and disciplined practice.

Such a science does not discard empirical inquiry. It extends it, aligning outer observation with inner realization. It recognizes that the ultimate questions—“Why are we here? What is worth living for? What is the purpose of the universe?”—cannot be answered by measurement alone, but require the cultivation of wisdom.

The courage to ask “Why”

We live in an era saturated with data but starving for meaning. Science has given us power, but not wisdom. It describes how things work, but not why they exist.

The Bhāgavata tradition reminds us that true knowledge is not only about precision—it is about purpose. Consciousness is not an illusion but the key to reality. Meaning, beauty, and love are not evolutionary quirks but the soul’s natural orientation.

Science remains essential. But if we want to live—not merely exist—we must be brave enough to ask the deeper questions it cannot answer.

Why are we here?

What does it mean to be conscious?

What is worth living for?

These are not questions for instruments alone. They are questions for insight, humility, and the integration of all ways of knowing.