Layers of identity in the Bhagavata–Vedic Framework

The Bhagavata model, arising from the wider Vedic philosophical corpus, provides a detailed map of identity and its layers. Instead of collapsing everything into the brain, it distinguishes at least three dimensions:

The Physical Body (sthūla-śarīra): The outer vehicle, composed of the five elements—earth, water, fire, air, and ether. It enables interaction with the tangible world but is temporary and perishable.

The Subtle Body (sūkṣma-śarīra): A more refined structure, consisting of mind (manas), intelligence (buddhi), and false ego (ahaṅkāra). This is the interface through which perception, thought, and identity operate.

- Manas (Mind): Processes sensory input, generates desires and doubts, and shifts attention between alternatives. Restless and reactive, it is responsible for both distraction and emotional flow.

- Buddhi (Intelligence): The discerning faculty that evaluates, reasons, and decides. Properly aligned, it can direct the mind toward clarity and truth.

- Ahaṅkāra (False Ego): The illusory sense of “I” that identifies with body, mind, and possessions. It gives rise to pride, fear, and attachment, masking the true self.

The True Self (ātmā): The eternal, conscious witness. It is distinct from both physical and subtle coverings—the experiencer that observes without being conditioned by them.

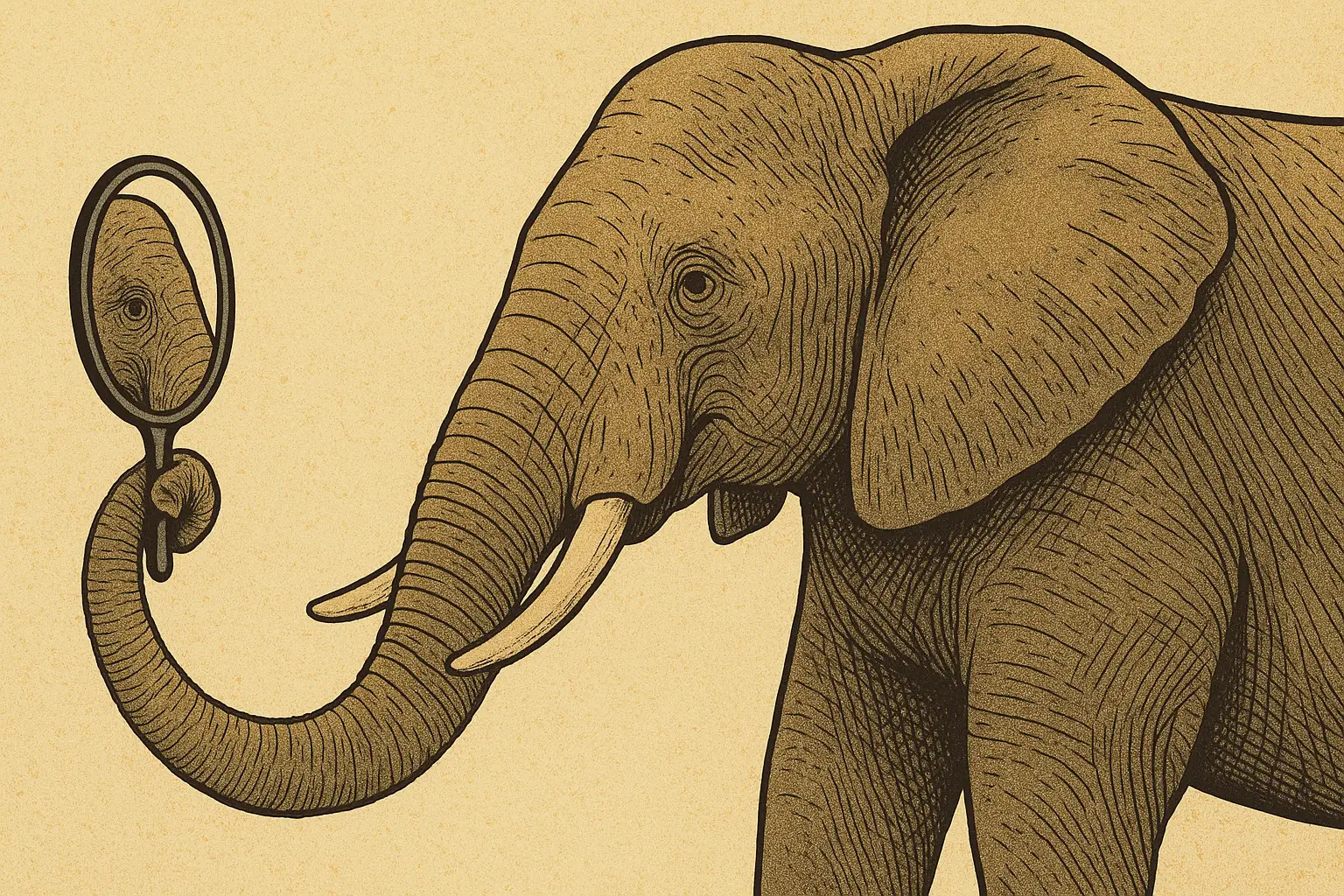

This model reframes our daily experience. When you notice anger arising within you, that act of noticing reveals a distinction between the emotion and the observer of it. The observer—the one who is aware of thought, mind, and body—is the ātmā.

The Bhagavad-gītā (2.13) explains:

“Just as the embodied soul continually passes in this body, from childhood to youth to old age, the soul similarly passes into another body at death. The wise are not deluded by this.”

The dehī, or embodied self, remains constant through changing bodily and mental states. The unchanging witness is the ātmā.

The Ātmā as Sat–Cit–Ānanda

Bhagavata philosophy defines the ātmā by three intrinsic qualities:

- Sat (Eternal Existence): The ātmā is unborn, indestructible, and beyond time. Unlike the physical body, which arises and perishes, the ātmā endures.

- Cit (Conscious Awareness): The ātmā is self-luminous, the very ground of experience. It does not merely compute information; it knows and experiences.

- Ānanda (Innate Bliss): The ātmā naturally seeks joy, relationship, and fulfillment. Our universal longing for happiness, meaning, and love reflects this intrinsic nature.

These qualities explain much about human behavior. Our recoil from death expresses sat, our hunger for truth reflects cit, and our search for connection reveals ānanda. These impulses are not accidental—they are the self’s essence pressing through layers of conditioning.

Yet the false ego (ahaṅkāra) overlays this essence, convincing us that we are the temporary body, the restless mind, or the social roles we occupy. Like a gamer lost in an avatar, we forget we are the one holding the controller.

The Mind–Body Problem revisited

Western philosophy has long wrestled with the relationship between mind and matter. Descartes famously divided them into two substances. Modern neuroscience, however, largely collapses the mind into the brain. Yet this leaves the “hard problem of consciousness” unresolved: how do subjective experiences arise from physical processes?

The Bhagavata–Vedic response is categorical: they don’t. Consciousness does not emerge from matter because it belongs to a different order of reality. The Bhagavad-gītā (7.4–5) draws the distinction:

“Earth, water, fire, air, ether, mind, intelligence, and ego—these eight constitute My separated material energies. But besides these, O mighty-armed Arjuna, there is another, superior energy of Mine—the living beings who are exploiting the resources of this material nature.”

Here, mind and intellect are classified as material energies, whereas the conscious self is described as a distinct, superior principle. The ātmā engages the world through subtle and gross instruments but remains ontologically different from them.

This reframes neuroscience itself. Just as a driver uses a car to navigate but is not the car, the ātmā uses the mind and brain as instruments but is not reducible to them.

The practical implications of the Bhagavata–Vedic model

Why does it matter whether we are brains or eternal selves? Because our answer shapes the very structure of society.

- Education: If we are machines, education is programming. If we are ātmās, education becomes a sacred task of awakening—developing intellect, character, and spiritual realization.

- Health: If we are bodies, health is maintenance. If we are ātmās, health becomes harmony between body, mind, and soul.

- Ethics: If we are matter, ethics is social convention. If we are ātmās, ethics arises from intrinsic dignity by recognizing that all living beings are ātmās in essence, resulting in our kinship with all life.

- Justice: If we are reducible to brain chemistry, justice becomes behavioral control. If we are ātmās, justice is transformation, restoring harmony to souls in community.

This difference is not abstract. It redefines love, meaning, and responsibility. If emotions are just chemicals, then love is reducible to oxytocin. But if we are ātmās, love is the expression of our eternal essence. Thus, the ātma paradigm is not an abstract point of view; rather, it has a direct and meaningful impact on our daily lives, both personally and societally.

Rediscovering the Self

The Bhagavata–Vedic model is not meant as dogma but as a practical science of self-realization. The practices of yoga—ethical living, meditation, devotion, and disciplined introspection—are methods for reconnecting with our eternal self.

The goal is to peel away false identifications, to move from being lost in the avatar of body and mind toward awareness of the ātmā. When we live from that place, we recover our original nature: eternal, self-aware, and blissful.

This is not about rejecting modern science but expanding it. Neuroscience explains correlations between brain states and mental functions, but the Bhagavata–Vedic framework supplies the missing piece: the conscious witness. By integrating both, we move toward a fuller science of life—one that honors both objectivity and lived experience.

From reduction to realization

The question is not simply what causes consciousness? but what am I, truly?

Reductionist views strip away meaning, reducing us to machines animated by chemistry. The Bhagavata perspective, in harmony with Vedic insight, restores dignity—showing us as eternal conscious beings with intrinsic purpose. In this light, the study of consciousness is not only a philosophical problem but a human imperative.

The ātmā is not a hypothesis but the immediate fact of awareness, the witness behind every thought and perception. To know this is not merely to solve a puzzle but to awaken to who we are.