What science still can’t explain

Despite breathtaking advances in neuroscience, one mystery remains untouched at its core: why are we conscious at all? Scientists can now map neural regions for memory, decision-making, emotion, and sensory processing with exquisite precision. They can observe the firing of neurons in response to pain or pleasure, trace circuits associated with learning, and even simulate aspects of cognition with artificial intelligence.

Yet none of this addresses the central question: why do these processes feel like anything from the inside? Why does a cascade of electrical and chemical signals create the redness of red, the pang of grief, or the awe of hearing a symphony? This puzzle—the “hard problem of consciousness,” as philosopher David Chalmers named it—remains unresolved, perhaps unresolvable, within the physicalist worldview.

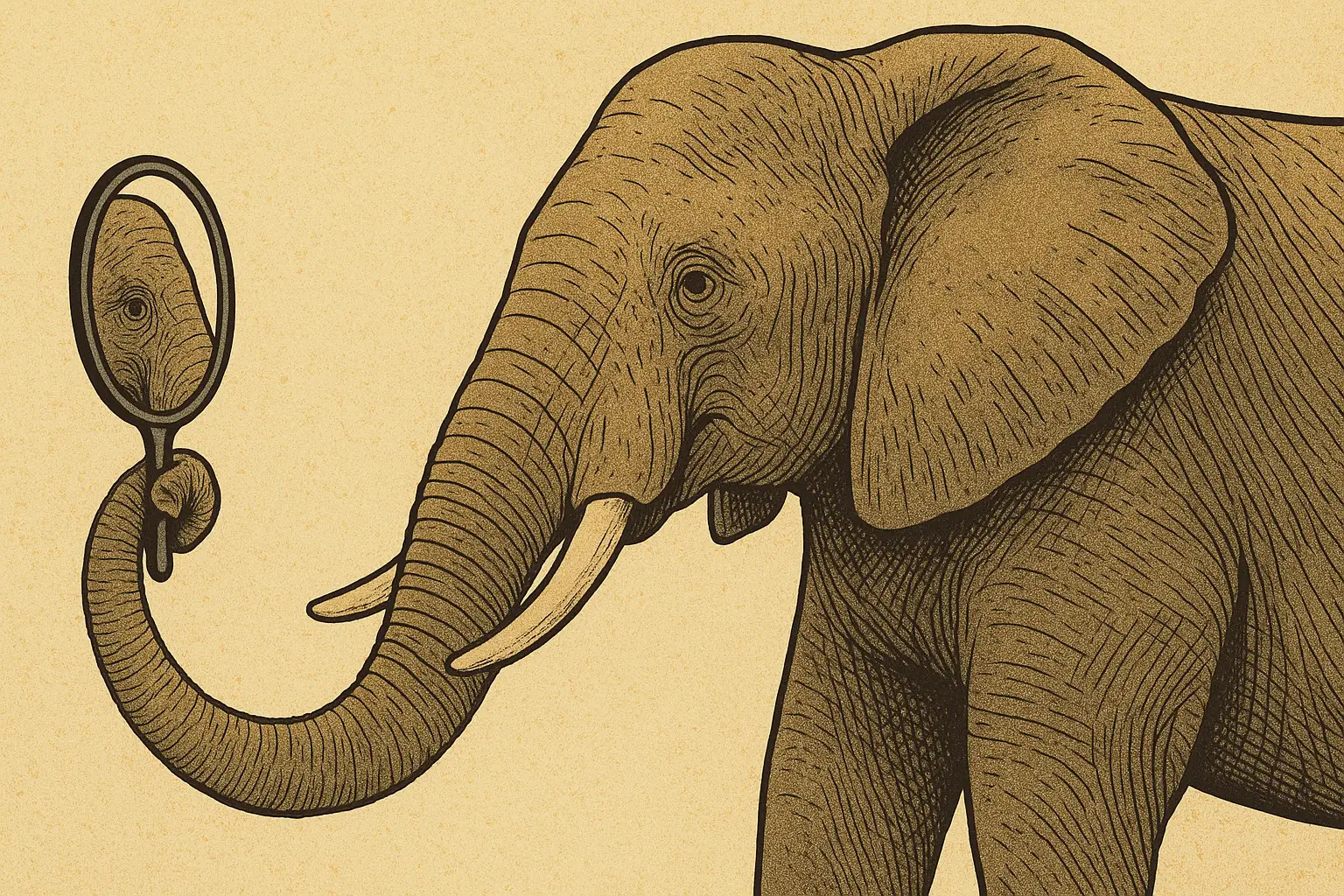

The difficulty lies not in understanding the mechanics of the brain but in bridging the gap between third-person description and first-person experience. Science can measure correlations between neural activity and reported states of awareness, but it cannot access the intrinsic quality of that awareness itself.

To many, the hard problem is more than a technical gap—it may be a fundamental limitation of the physicalist paradigm. If all that exists is physical and measurable, then subjectivity, which by definition is not measurable from outside, may forever remain an anomaly.

The limits of reductionism

Physicalist theories have tried to solve consciousness in various ways. Some argue it “emerges” once matter reaches a certain level of complexity, as in the human brain. Others propose it is an illusion—nothing more than the brain tricking itself into thinking there is a “self”. Still others treat it as epiphenomenal, a harmless side effect of computation that plays no causal role.

But each of these approaches reduces consciousness to something else—computation, chemistry, or biology. Reduction, however, is not explanation. To say that consciousness is what happens when neurons fire in complex patterns is akin to saying music is what happens when strings vibrate. True, but incomplete. It leaves untouched the most intimate aspect of experience: that it is experienced at all.

Science can describe your brain’s response to a sunset, but it cannot feel the beauty you see. It can monitor cortisol levels during grief, but it cannot share your sorrow. Experience is not an object in the world. It is the subject of all perception.

This is precisely where the Bhagavata perspective begins.

The Vedic response: consciousness as primary

In the Bhagavata philosophy and the broader Vedic tradition, consciousness is not the last thing to emerge from matter; it is the first principle of reality. The self, or ātma, is not a product of brain processes but the irreducible experiencer behind them.

Vedic metaphysics distinguishes between the self and its instruments. The body is the gross vehicle, and the mind (with its faculties of manas [sensory processing], buddhi [intellect], and ahaṅkāra [ego]) is a subtle material tool. But the ātma—the conscious self—is distinct. It is the witness, the subject who experiences the mind and body but is never reducible to them.

The Bhagavad-gītā (2.20) is unambiguous:

“For the ātma there is neither birth nor death at any time. He has not come into being, does not come into being, and will not come into being. He is unborn, eternal, ever-existing, and primeval. He is not slain when the body is slain.”

This is not metaphor but metaphysics. Consciousness is eternal, irreducible, and ontologically prior to matter.

Neuroscience reconsidered

This view does not deny the findings of neuroscience. Clearly, the brain is implicated in conscious processes: damage to the cortex affects perception, anesthesia suspends awareness, and psychedelic compounds radically alter experience. But correlation does not equal causation.

The Vedic response is to compare the brain to a radio receiver. Damage the radio, and the sound distorts—but that does not mean the music originates in the circuitry. Likewise, the brain processes, filters, and transmits information, but the experiencer of that information is the ātma.

Neuroscience, in this analogy, is studying the circuitry with great success. But until it acknowledges the signal itself—the conscious self—it risks mistaking the medium for the source.

Consciousness as universal

Interestingly, some contemporary thinkers are converging toward positions more consistent with Vedic thought than with classical materialism. Theories like panpsychism, integrated information theory (IIT), and quantum consciousness suggest that consciousness may be a basic property of the universe rather than an emergent accident.

Vedic texts long ago articulated this. The ātma, or individual conscious unit, is eternal. Consciousness pervades life in all its forms, from the simplest organism to the most complex. Awareness is not a rare product of biological evolution but the defining feature of reality itself.

Whereas materialism views consciousness as a latecomer in the cosmos, Bhagavata philosophy and Vedānta in general, sees it as ever-present, shaping, animating, and participating in the unfolding of reality.

Why this matters

The implications of this paradigm shift are profound. If consciousness is foundational:

- Education must embrace not only objective facts but also subjective cultivation—self-awareness, meditation, and ethical development.

- Medicine must address not only biochemical imbalances but the existential dimension of suffering and meaning.

- Philosophy and science must expand their epistemologies to include inner observation as a valid form of knowledge.

In a world plagued by nihilism, alienation, and reduction of human beings to mechanisms, this recognition of consciousness as primary offers a way back to meaning. It affirms human dignity, creativity, and purpose—not as illusions, but as intrinsic features of existence.

Toward a deeper science

If neuroscience continues to treat consciousness as an emergent object, it may chase shadows indefinitely. But if we allow consciousness to be what it already is—the irreducible subject of knowing—we open the door to a more comprehensive science.

This is not a retreat into mysticism. It is an expansion of method. Just as physics learned to move beyond Newtonian mechanics into relativity and quantum theory, so too must the science of mind move beyond materialism into a paradigm where subjectivity itself becomes central.

The Vedic response invites precisely this: a dialogue between inner experience and outer observation, between timeless wisdom and modern research, between self and cosmos.

Perhaps the real “hard problem” is not explaining consciousness at all—but accepting that consciousness explains us.