Modern physics has an odd habit of stumbling into philosophy.

It begins with equations about black holes, spacetime, and information and ends by asking questions that sound strangely ancient: What does it mean for something to exist? Can reality be described without reference to a knower? Is there such a thing as a “view from nowhere”?

A new article in Quanta Magazine (link) describes recent paradox emerging from theoretical physics sharpens these questions into something both elegant and unsettling. In trying to describe the universe as a complete, self-contained whole, without assuming any observers or external vantage point, physicists (Harlow et al., 2025) found that the universe may collapse into something like informational emptiness.

Not empty of matter, perhaps. Not empty of space. But empty of meaningful structure.

And that is a very different kind of emptiness.

A Strange Result From the Physics of Black Holes

Over the last few decades, black holes have become far more than astronomical curiosities. They have become conceptual laboratories: places where our most fundamental assumptions about spacetime and information are put under extreme stress.

One of the most famous questions in modern physics is deceptively simple: if something falls into a black hole, and the black hole eventually evaporates, what happens to the information?

Resolving that question forced physicists to develop new ways of thinking about boundaries, quantum states, and the nature of information itself. These tools were designed to explore the deepest seams of reality — places where gravity and quantum physics overlap.

Then someone asked the obvious next question: what happens if we apply these same tools not to black holes, but to the universe?

Not the universe as we casually think of it, filled with galaxies, observers, and measuring devices, but the universe as a total system, described in one complete sweep. No external frame. No “outside.” No observer assumed.

The result was surprising enough to be called a paradox.

The “One-State” Universe

Imagine a universe with no edge. A universe that is closed in the sense that there is nowhere to stand outside it. Many cosmological models are built this way. The familiar analogy is the surface of a sphere: finite, but without a boundary.

Physicists tried to describe such a universe using the mathematical language of quantum theory. They were asking, in effect: how many possible states can such a universe take?

And the equations hinted at an answer that feels almost impossible to accept: the universe might have only one possible state.

Not one likely state among many. Not one state that dominates statistically. One state, total.

If true, the consequence is stark. Information, in the simplest sense, depends on alternatives. A coin flip carries information because it could land heads or tails. A message carries information because it could have been arranged differently. Meaning depends on distinction; distinction depends on possibility.

A universe with only one allowed state is, in this sense, a universe without informational content. It becomes like a book with one blank page. It may exist, but it cannot encode a story.

And yet our universe clearly does encode a story. It has structure. It has history. It has memory, variation, and change.

So what is going on?

Why This Isn’t Just a Mathematical Quirk

It would be tempting to dismiss this as an artifact of overly simplified models — a strange byproduct of the kind of idealized universes theorists explore on a chalkboard.

But the unsettling part is that the theme doesn’t disappear easily. Variations of the result appear across related lines of research. And the methods that give rise to it are not fringe ideas; they sit near the center of modern work on quantum gravity.

The paradox points to something deeper than a calculation error. It hints at a conceptual limit: when physics tries to describe the universe as a complete whole, without any internal perspective, the description collapses into triviality.

Not because the universe is physically empty, but because it becomes informationally undifferentiated. It is too unified, too uncarved, too seamless to generate internal distinctions.

Which raises a natural question: what restores complexity?

Why the Observer Matters

The moment we use the word observer, misunderstandings rush in. Modern culture has loaded that word with confusion: “consciousness creates reality,” “the mind collapses the wavefunction,” and other half-digested slogans.

That is not what this line of physics is saying.

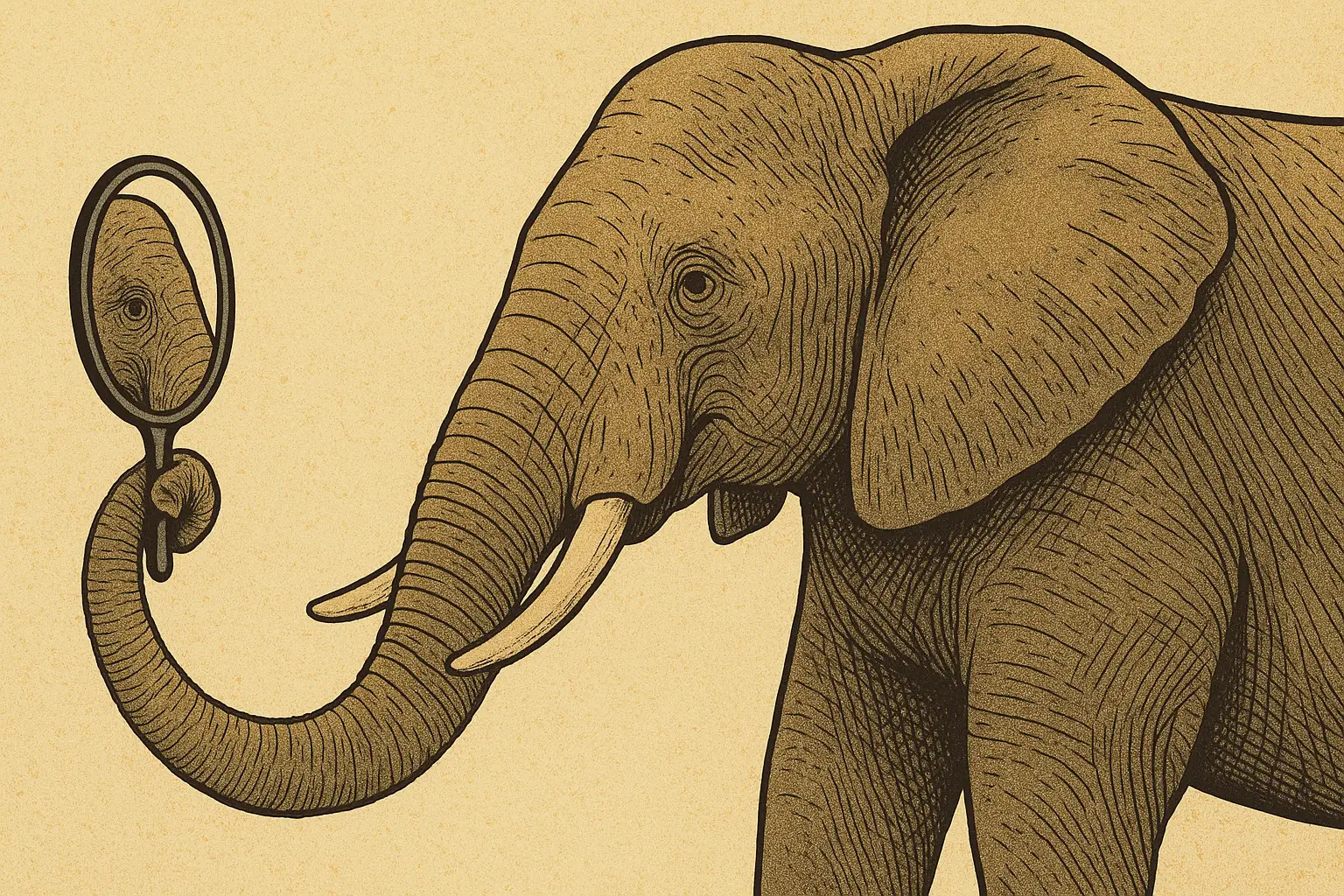

Here, observer means something far more basic and structural: a standpoint within reality that makes distinctions possible.

An observer introduces a boundary, not necessarily a physical barrier, but a boundary of description. Think of it like a meaningful separation between “here” and “there,” “inside” and “outside,” “self” and “world.”

In normal physics, we describe systems from the outside. We measure planets, molecules, and particles as external observers. But the universe itself has no outside. There is no cosmic laboratory bench.

So if physics tries to describe the universe “objectively” as if from an impossible perspective, a point of view that belongs to no one, it may be trying to do something incoherent.

This is one way to interpret the paradox: without an observer, there is no partition of reality; without partition, no distinction; without distinction, no information.

The universe becomes “one state” not because it contains nothing, but because it becomes too undivided to be meaningfully described. Like an infinite ocean with no shoreline, no waves, and no reference points — an expanse so smooth that direction and feature lose their meaning.

Introduce an observer, and suddenly relationships become possible. Self and world. Measured and measuring. Subject and object. Complexity returns because the universe becomes legible from within.

It becomes revealed through relational structure.

A Relational Universe

This pushes us toward a worldview that has quietly been growing in physics for over a century: relationality.

In relativity, motion depends on perspective. So does time. Even simultaneity, the idea of events “happening at the same time”, depends on the observer’s frame.

But the cosmic paradox suggests a deeper extension of that insight: perhaps even the information content of the universe is not something that exists independently of standpoint.

Perhaps information is not merely contained in reality like coins in a jar, but generated through the existence of meaningful distinctions, and meaningful distinctions arise relationally.

In this view, the universe is not a single block of being that can be fully described “from nowhere.” It is a network of relationships that becomes intelligible only when there is a perspective within it.

Which is precisely where the philosophical resonance becomes impossible to ignore.

Resonance With Vedic Thought: Knower, Known, and Knowledge

In many Vedic and Vedantic traditions, reality is not framed as a purely objective scene unfolding in front of no one. It is understood through a triad: the knower, the known, and the act of knowing.

This triad is not treated as a psychological detail. It is treated as an ontological structure. A deep pattern by which existence becomes a meaningful world.

In this view, removing the knower is not a small subtraction. It dissolves the very conditions under which distinction and meaning arise.

This does not mean the world is imaginary. It does not require naïve idealism. Rather, it suggests something subtler and more durable: the world as an intelligible reality is inseparable from the presence of the witness.

Even the Bhagavad Gītā describes the self not merely as an object among objects, but as the seer: the principle by which experience becomes possible. Later Vedantic thought refines this further, presenting consciousness not as a product inside the universe, but as the luminous condition in which the universe becomes known.

Against that background, the cosmic paradox reads like an unexpected echo: when physics tries to remove the standpoint of knowing entirely, the universe collapses into undifferentiated abstraction.

Not because the knower invents reality, but because without the knower, reality cannot become a world. A universe may be physically vast and still be informationally null if there is no standpoint within it.

A Deeper Invitation

We should be careful. This paradox does not prove metaphysics. Physics is still developing its understanding of closed universes and quantum gravity. The technical result may evolve, and the paradox may eventually be resolved in a way that no longer speaks explicitly of observers.

But even if the details change, the pressure remains: a purely objective “view from nowhere” may not be coherent.

And that is not merely a philosophical flourish. It is a demand placed on our concept of reality. It invites us to consider that existence is not only about what is “out there,” but also about what can be known — and how.

Perhaps reality is not merely being, but being-known.

Perhaps consciousness is not an accidental byproduct of matter, but a necessary dimension of intelligibility — the witness through which distinctions arise and meaning becomes possible.

If modern physics is pointing even faintly in this direction, it aligns with an ancient inquiry that remains as relevant as ever.

The ultimate question is not only “What exists?” but “Who is the one to whom existence appears?”

And perhaps that is the true consequence of the cosmic paradox: a universe without observers may not be physically empty, but it may be empty of the only thing that makes it a world.